December 12, 2025

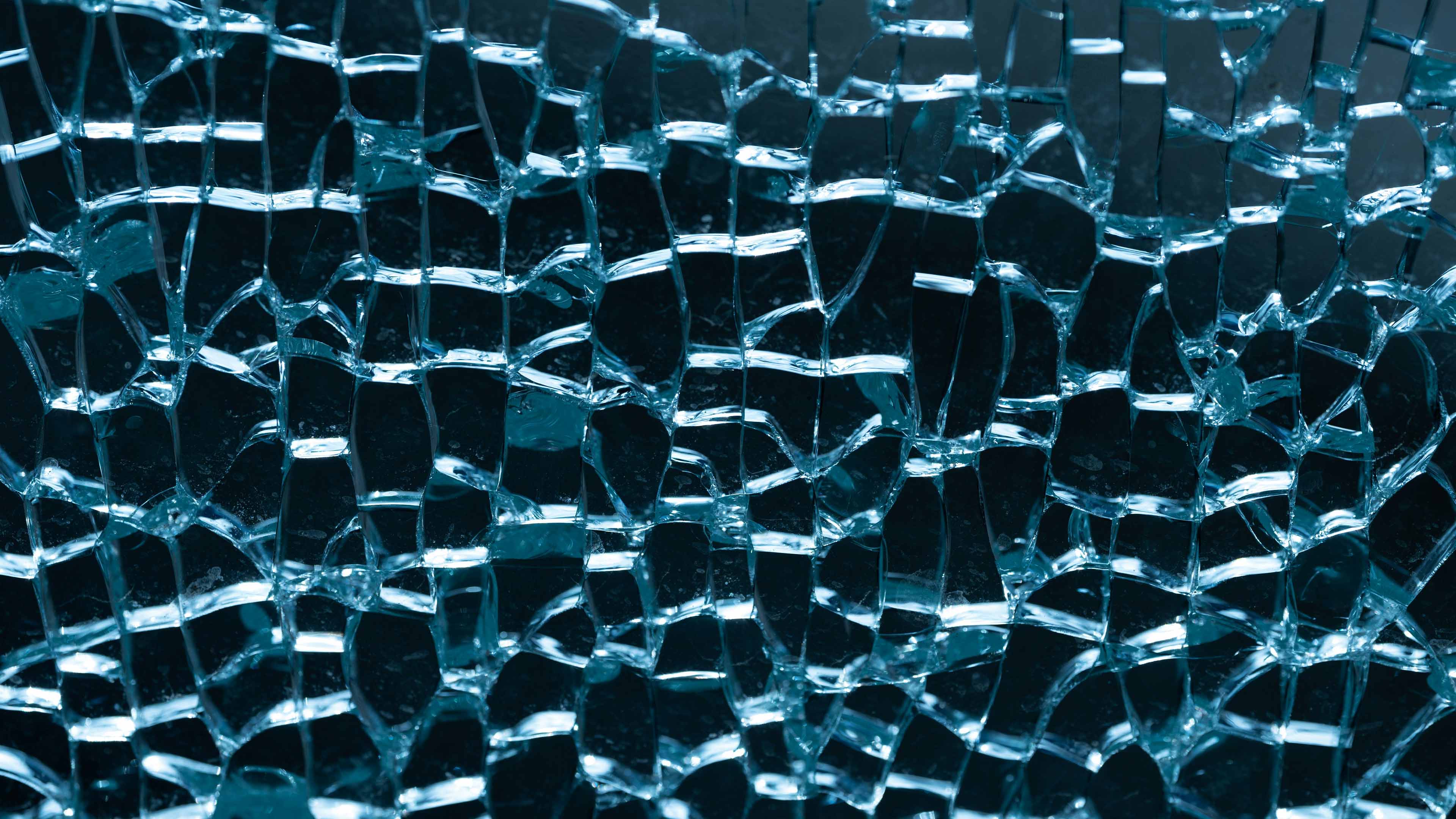

Design is fragmenting.

Design is fragmenting.

December 12, 2025

Design is fragmenting.

It has never been harder to answer a seemingly simple question: what is design?

Not because we lack definitions, but because we have too many of them. Into roles, aesthetics, specializations, trends, and sub-niches, contemporary design feels increasingly fragmented. While this expansion opens doors, it also creates uncertainty, confusion, and a persistent sense of displacement, especially for those entering the field.

Questions like What is my actual role? Which skills really matter? What tools deserve my time? Who am I designing for? And perhaps the most revealing question of all, how do I define myself professionally? are not new. What has changed is the landscape in which they are being asked.

With industrialization and the rise of mass production, work became divided, optimized, and broken into smaller, specialized tasks. This logic proved extremely effective in manufacturing. Over time, it expanded far beyond factories, shaping how we organize labor, knowledge, and eventually, design itself.

Today, the term “designer” unfolds into countless job titles: UX Designer, UI Designer, Product Designer, Visual Designer, Interaction Designer, Motion Designer, Brand Designer, Graphic Designer, and so on. What once described a broad practice is now segmented into narrowly defined roles, each with specific responsibilities, tools, and expectations.

Specialization, in this context, often measures value through repetition. Years spent refining a specific function can build technical depth, but they also raise an important question: what kind of thinking does this structure encourage?

When design is reduced to execution, it becomes detached from decision-making. The designer no longer helps define the problem, but is brought in to shape its surface. In this arrangement, design risks becoming a purely operational function, which is easily replaceable as tools, platforms, or business needs change.

Aesthetics, trends, and the accelerated present

Alongside functional fragmentation, we are also experiencing aesthetic fragmentation at an unprecedented scale.

What once emerged as cultural movements now often appears as fleeting micro-trends. Visual languages rise, circulate, and disappear at high speed, fueled by algorithms, social platforms, and shrinking attention cycles.

Platforms like TikTok have intensified this phenomenon. Every day, a new “-core” aesthetic surfaces, offering another identity to adopt, reference, or abandon. Within graphic design alone, radically different styles coexist - Y2K, brutalism, minimalism, maximalism, and countless hybrids - often without meaningful dialogue between them.

Unlike earlier periods in design history, there is no dominant direction or shared narrative. Instead, the field organizes itself into communities, each with its own visual codes, references, and values. All represent fragments.

This decentralization brings diversity and creative freedom. But it also makes it harder to articulate what design means as a collective practice.

The impact on professionals and newcomers

For those already working in the field, this landscape can lead to over-dependence on highly specific roles. For newcomers, the effect can be even more disorienting.

There are too many paths, too many niches, too many tools, too many aesthetics, and very little room to pause or make mistakes. The pressure to specialize early and define oneself quickly can push designers away from experimentation and critical thought.

In this environment, design risks drifting away from its core purpose: understanding complex problems and shaping meaningful responses, rather than simply delivering polished outputs.

Synthesis as a central skill

In a fragmented ecosystem, the most valuable ability may not be mastering a single piece, but connecting many of them.

Rather than diving endlessly into one narrow slice, relevance increasingly belongs to those who can move between disciplines, read context, and transform scattered inputs into coherent systems. Those who question the problem before accepting the solution. Those who see design as a way of thinking, not just producing.

This does not mean rejecting specialization, trends, or aesthetics. They are part of the current landscape. But they may need to be balanced with a broader perspective.

A pause for perspective

Amid so many definitions, perhaps the more useful question is not “Which niche do I belong to?” but “What kind of perspective am I developing?”

Design has never had more tools, visibility, or potential paths. At the same time, it has never felt harder to describe in a single sentence.

Maybe it doesn’t need to be fully defined right now.

Maybe it’s enough to slow down, step back, and remember that before job titles, trends, or software, design has always been a way of thinking.

It has never been harder to answer a seemingly simple question: what is design?

Not because we lack definitions, but because we have too many of them. Into roles, aesthetics, specializations, trends, and sub-niches, contemporary design feels increasingly fragmented. While this expansion opens doors, it also creates uncertainty, confusion, and a persistent sense of displacement, especially for those entering the field.

Questions like What is my actual role? Which skills really matter? What tools deserve my time? Who am I designing for? And perhaps the most revealing question of all, how do I define myself professionally? are not new. What has changed is the landscape in which they are being asked.

With industrialization and the rise of mass production, work became divided, optimized, and broken into smaller, specialized tasks. This logic proved extremely effective in manufacturing. Over time, it expanded far beyond factories, shaping how we organize labor, knowledge, and eventually, design itself.

Today, the term “designer” unfolds into countless job titles: UX Designer, UI Designer, Product Designer, Visual Designer, Interaction Designer, Motion Designer, Brand Designer, Graphic Designer, and so on. What once described a broad practice is now segmented into narrowly defined roles, each with specific responsibilities, tools, and expectations.

Specialization, in this context, often measures value through repetition. Years spent refining a specific function can build technical depth, but they also raise an important question: what kind of thinking does this structure encourage?

When design is reduced to execution, it becomes detached from decision-making. The designer no longer helps define the problem, but is brought in to shape its surface. In this arrangement, design risks becoming a purely operational function, which is easily replaceable as tools, platforms, or business needs change.

Aesthetics, trends, and the accelerated present

Alongside functional fragmentation, we are also experiencing aesthetic fragmentation at an unprecedented scale.

What once emerged as cultural movements now often appears as fleeting micro-trends. Visual languages rise, circulate, and disappear at high speed, fueled by algorithms, social platforms, and shrinking attention cycles.

Platforms like TikTok have intensified this phenomenon. Every day, a new “-core” aesthetic surfaces, offering another identity to adopt, reference, or abandon. Within graphic design alone, radically different styles coexist - Y2K, brutalism, minimalism, maximalism, and countless hybrids - often without meaningful dialogue between them.

Unlike earlier periods in design history, there is no dominant direction or shared narrative. Instead, the field organizes itself into communities, each with its own visual codes, references, and values. All represent fragments.

This decentralization brings diversity and creative freedom. But it also makes it harder to articulate what design means as a collective practice.

The impact on professionals and newcomers

For those already working in the field, this landscape can lead to over-dependence on highly specific roles. For newcomers, the effect can be even more disorienting.

There are too many paths, too many niches, too many tools, too many aesthetics, and very little room to pause or make mistakes. The pressure to specialize early and define oneself quickly can push designers away from experimentation and critical thought.

In this environment, design risks drifting away from its core purpose: understanding complex problems and shaping meaningful responses, rather than simply delivering polished outputs.

Synthesis as a central skill

In a fragmented ecosystem, the most valuable ability may not be mastering a single piece, but connecting many of them.

Rather than diving endlessly into one narrow slice, relevance increasingly belongs to those who can move between disciplines, read context, and transform scattered inputs into coherent systems. Those who question the problem before accepting the solution. Those who see design as a way of thinking, not just producing.

This does not mean rejecting specialization, trends, or aesthetics. They are part of the current landscape. But they may need to be balanced with a broader perspective.

A pause for perspective

Amid so many definitions, perhaps the more useful question is not “Which niche do I belong to?” but “What kind of perspective am I developing?”

Design has never had more tools, visibility, or potential paths. At the same time, it has never felt harder to describe in a single sentence.

Maybe it doesn’t need to be fully defined right now.

Maybe it’s enough to slow down, step back, and remember that before job titles, trends, or software, design has always been a way of thinking.

SHARE